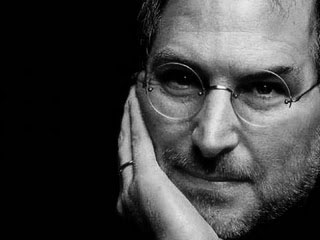

Your technology doesn't just change the method that you communicate, it changes what you talk about and how you do it. Not only that, but technology also shapes our society and culture. So, whoever is shaping our culture and technology is shaping your world in someway, whether you know it or not. Steve Jobs wasn't the master of the universe - clearly - but he was one of the idea leaders of our day, so understanding his ideas (and the many other thought leaders that are vying for space in our lives) actually matters.

I'm not an expert on Steve Jobs, the author of this article likely isn't either, but it will get your thoughts turning at a minimum. One of the more powerful sections was a comparison of Jobs's Stanford commencement speech (see last week's post) and a Martin Luther King Jr. speech:

"Mr. Jobs's final leave of absence was announced this year on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. And, as it happened, Mr. Jobs died on the same day as one of Dr. King's companions, the Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth, one of the last living co-founders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Dr. King, too, had had a close encounter with his own mortality when he was stabbed by a mentally ill woman at a book signing in 1958. He told that story a decade later to a rally on the night of April 3, 1968, and then turned, with unsettling foresight, to the possibility of his own early death. His words, at the beginning, could easily have been a part of Steve Jobs's commencement address:

"Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now."

But here Dr. King, the civic and religious leader, turned a corner that Mr. Jobs never did. "I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And so I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything, I'm not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!"

Is it possible to live a good, full, human life without that kind of hope? Steve Jobs would have said yes in a heartbeat. A convert to Zen Buddhism, he was convinced as anyone could be that this life is all there is. He hoped to put a "ding in the universe" by his own genius and vision in this life alone—and who can deny that he did?

But the rest of us, as grateful as we are for his legacy, still have to decide whether technology's promise is enough to take us to the promised land. Is technology enough? Has the curse truly been repealed? Is the troublesome world simply awaiting another Steve Jobs, the evangelist of our power to unfold our own possibilities?

And, correspondingly, was the hope beyond themselves, and beyond this life, that animated Dr. King and his companions merely superfluous to the success of their cause, an accident of religious history rather than a civic necessity?

For people of a secular age, Steve Jobs's gospel may seem like all the good news we need. But people of another age would have considered it a set of beautifully polished empty promises, notwithstanding all its magical results. Indeed, they would have been suspicious of it precisely because of its magical results.

And that may be true of a future age as well. Our grandchildren may discover that technological progress, for all its gifts, is the exception rather than the rule. It works wonders within its own walled garden, but it falters when confronted with the worst of the world and the worst in ourselves. Indeed, it may be that rather than concealing difficulty and relieving burdens, the only way forward in the most tenacious human troubles is to embrace difficulty and take up burdens—in Dr. King's words, to embrace a "dangerous unselfishness.""

No comments:

Post a Comment